The Peter Principle- Why Great Salespeople can make Lousy Managers

The Promotion Trap: How Mediocrity Rises and Mastery Stalls

Introduction: A Theory That Refused to Stay Satirical

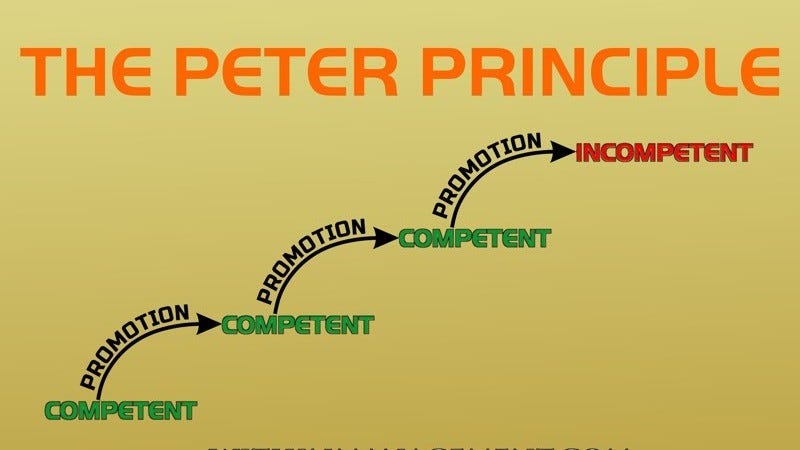

In 1969, Canadian educator Laurence J. Peter introduced the world to a peculiar and unsettling idea: in a hierarchy, every employee tends to rise to their level of incompetence. It was satire, yes—but also searingly accurate. The Peter Principle was meant to be a humorous theory, a poke in the ribs of management orthodoxy. But the joke wore off. The theory aged like prophecy.

What Peter revealed wasn’t just a management quirk. He exposed an endemic flaw in how organizations function, how humans chase prestige, and how institutions confuse motion with progress. In a world obsessed with climbing, the Peter Principle offered a bleak truth: not every ascent is an achievement. Some are just misplacements with better pay.

Today, with flatter hierarchies, algorithmic promotions, and the cult of personal branding, Peter’s ghost walks every HR department and executive suite. What was once satirical is now operational.

Part I: The Anatomy of a Misfit

Every miscast promotion has a backstory, and most of them start in the mirror. The psychological cocktail behind the Peter Principle is a mix of the Dunning-Kruger effect (where people overestimate their competence), the halo effect (where success in one area unfairly boosts perceived ability in others), and a sprinkle of LinkedIn-fueled narcissism.

Take the engineer who ships perfect code, gets promoted, and suddenly has to manage people who write imperfect code. They once solved problems with clarity; now they sit in meetings, soothing egos. Or the startup founder who dazzles investors but implodes once actual management is required.

The fallacy of transferable success is our favorite professional myth. We see someone excel at X and assume they’ll be just as brilliant at Y. We’re wrong more often than we admit.

It’s worse in certain sectors. In tech, for example, developers often get promoted to lead teams they once worked within, expected to trade debugging for diplomacy. In politics, skilled communicators become poor governors. In academia, brilliant researchers are handed administrative empires they neither want nor understand. Each time, success gets weaponized against the individual.

Part II: Promotions Gone Wrong – Expanded Case Studies

History’s archives are bloated with promotion flops. George McClellan was a master logistician but a battlefield catastrophe. Lincoln’s army was prepared, equipped, and perfectly idle.

Anthony Scaramucci is the corporate version of a Red Bull-fueled tweetstorm. His rise and fall as White House Communications Director was a compressed course in the dangers of mistaking media savvy for managerial acumen.

Elizabeth Holmes, once hailed as the next Steve Jobs, showed how charisma can override competence for dangerously long periods. Theranos was a case study in systemic failure to distinguish vision from vapor.

And let’s not forget the fiction that reflects us. David Brent from The Office and his American cousin Michael Scott are both comedic proof that enthusiasm and earnestness are not proxies for aptitude.

WeWork’s Adam Neumann? The Peter Principle on a private jet, coasting on vibes, vision, and venture capital until reality crashed the IPO party.

Part III: Performance vs. Potential – Where It All Falls Apart

Organizations are often drunk on KPIs. They promote performers based on past outputs with little attention to future fitness. But a sniper doesn’t always make a good general. Tactics are not strategy. Doing is not directing.

This confusion is compounded by the tyranny of corporate archetypes. We reward assertiveness over thoughtfulness, charisma over clarity, and confidence over competence. Boardrooms echo with repetition, not reflection.

Leadership potential should not be measured by how many boxes you tick—it should be assessed by how many blind spots you can see. Most promotions are awarded for what someone has done, not what they are likely to handle.

Part IV: Organizational Culture and Its Co-Conspirators

HR should be a filter. Too often, it’s just a funnel. Promotion tracks become reward systems instead of capability audits. This undermines not only productivity but inclusion.

DEI initiatives are harmed when underrepresented employees are vaulted too fast without mentorship and infrastructure. The result? Tokenism, burnout, and regression. We set people up to fail and then pretend it’s meritocracy.

Meanwhile, founder culture is fetishized. We mistake passion for wisdom. The CEO cult leads to executives who believe they’re infallible—and boards who are too scared to say otherwise.

Part V: Sectors in Crisis – The Peter Principle’s Damage Report

Tech is a sandbox of misfired promotions. Developers become VP Engineering without leadership experience. Suddenly, they’re drowning in budgets and burnout.

Academia suffers from the scholar-to-admin pipeline. Great minds in research become bureaucratic bystanders, spending more time in spreadsheets than seminars.

In healthcare, elite surgeons are given department control. Yet managing people, processes, and politics requires a different scalpel.

Government might be the worst offender. Policy nerds become policymakers. Bureaucrats become leaders. And sometimes, reality TV stars become Presidents.

Part VI: Neuroscience, Psychology, and Leadership Fit

Not all brains are wired for leadership. Executive roles come with cognitive demands—ambiguity tolerance, social reasoning, impulse control—that aren’t universal.

The best doers often suffer in executive roles due to increased cognitive load. Add emotional labor, decision fatigue, and organizational politics, and it’s no wonder burnout is epidemic at the top.

Leaders without self-awareness become tyrants with calendars. The absence of emotional intelligence creates moral injury in teams. Mistrust metastasizes.

Part VII: Rebuilding the Ladder

We need to decouple status from role. Companies like Atlassian and Basecamp offer dual tracks: individual contributor and people manager. Pay is equal. Prestige is equal. And sanity is preserved.

Step 1: Redesign career paths. Celebrate mastery without forcing hierarchy.

Step 2: De-risk demotions. Normalize the step-down. It’s not failure—it’s fit.

Step 3: Incentivize lateral moves. Horizontal growth is often more valuable.

Step 4: Reward real impact. Kill optics-driven promotion. Promote those who make others better, not just themselves richer.

Part VIII: The Personal Reckoning – Should You Even Be Promoted?

Take the climb audit. Are you good at what your next role demands? Or just chasing the title?

Consult mentors who will tell you the truth. Seek feedback that hurts. Because your ego might cost your team more than your silence.

It takes more courage to say "no" to a promotion than to accept it for the wrong reasons.

Part IX: Future-Proofing Promotion Models

AI is already entering performance review. But let’s train it to measure the right things.

Run leadership simulations. Use psychological vetting. Flatten hierarchies. Make the succession plan a public map, not a boardroom mystery.

We need new models. Transparent. Accountable. Humane.

Conclusion: Promotion is Not a Birthright

The climb is not the point. Impact is.

Fixing the Peter Principle isn’t an HR project. It’s a societal reckoning. We need to rethink what success means, who gets to lead, and why. Prestige should be earned by value, not velocity.

The Peter Principle wasn’t just a theory. It was a warning. Let’s finally heed it.

#LeadershipFail #PeterPrinciple #OrganizationalPsychology #ModernLeadership #ExecutiveInsights #ManagementTruths #CareerClimbers #CorporateCulture #PromotionTrap #WorkplaceWisdom #LeadershipDevelopment #TalentStrategy #PerformanceVsPotential #SuccessionPlanning #ImpactOverTitle